“Guest of Honour”, the inscrutable new film from Atom Egoyan, is a moral labyrinth that plays fast and loose with time, truth, and family. It’s a story where nobody ever seems to know quite the whole story, and what they do with half-truths, lies, and misconceptions will lead them down dark and destructive paths most difficult to return from.

Like Egoyan’s sublime masterpiece The Sweet Hereafter, this story is told out of order, gradually letting us to see the whole picture and all the players in it. We open on a young woman, Veronica (Laysla De Oliveira), visiting a priest, Father Greg (Luke Wilson) to discuss arrangements for her father’s funeral. In conversation that resonates with the elegiac banality of post-mortem truths, how the most shocking of scandals are deflated in death and the most embarrassing details of the deceased are nodded over casually in polite conversation, Veronica describes her late father, his flaws and strained relationships and uneasy, unspoken road back to the Church at the very end of his days.

Veronica is at ease with this priest. She takes advantage of the setting, an empty church music room, the comfort of daylight, and Father Greg’s own soothing presence, brilliantly conveyed by Wilson’s easy going magnanimity. It’s not exactly a confession for Veronica, but she will tell all, including her own sins and suspicions. We learn she was a music teacher. That she was accused of having an affair with one of her students, and though innocent, she plead guilty and requested the maximum sentence. De Oliveira, truly a discovery, is stunning in her frankness here, but that naked candor is the very point I mentioned earlier. Divorcing the pain of trauma from memory is not detachment, it’s history. And this is nothing if not a story about gaining perspective. By opening up so brazenly about her own life, Veronica is able to, at long last, confront certain truths that have stayed with her family for years and haunted her the greater part of her life. Now out of prison, she’s struggling to find her new direction, and sees her father at the center of it.

He is Jim, a restaurant heath inspector, an occupation that Father Greg casually describes with inadvertent brilliance, “That sounds like one of those jobs you always hear about, but never actually seeing anyone doing.” This is fitting. Jim is a quiet man who occupies a station in life unsung but necessary. It brings him no pleasure to shut a restaurant down, but in a story where duty and moral obligation supersede personal preference, it’s sometimes something he must do. He too has a complicated history, told in bits and pieces. We learn this reserved widower used to be a restauranteur himself, but after the death of his wife, he sought a more stable albeit less glamorous occupation.` He is driven in this story by a gnawing, unanswerable “Why?” He cannot believe his daughter would commit statutory rape, but nor can he wrap his head around why she would lie. He occupies now a world of doubt and frustration.

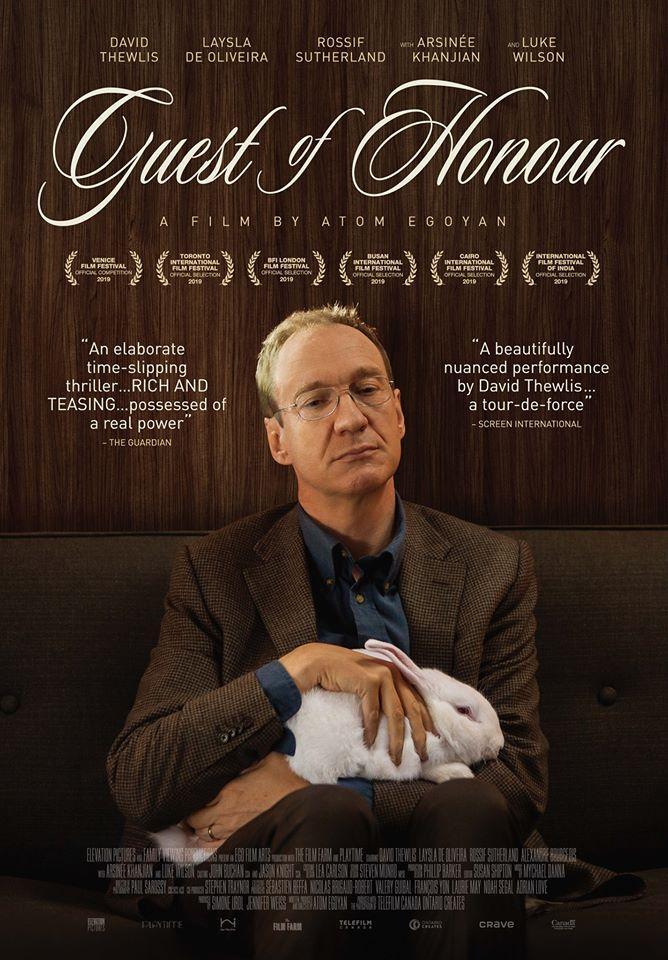

And he is played by David Thewlis in one of the most nuanced and unpredictable performances of the year. We see every aspect of his life and role he inhabits, as widower, public servant, culinary connoisseur, quiet Catholic, and music aficionado. He carries himself with a quiet dignity and reserved quality that threatens to burst at the seams when faced with the senseless in the role that matters most here, that of father. We can see echoes of Mitchell Stevens, Ian Holm’s distressed, resigned father in the Sweet Hereafter, and the pithy wordliness in taking authority where he has it calls to mind Thewlis’s own VM Varga from Fargo. It’s a powerful, painful role, because he is such a reserved man trying to hide his pain. He feels powerless in the face of the senseless, but the way he is drawn to use the little authority he does have, as a food inspector, comes as striking, the desperate act of a desperate man as his controlled world, including his own objectivity, falls apart around him.

Guilt is a curious, valuable, dangerous thing. It can be a burden that weighs people down and prevents closure. Certainly the characters here are living with the pain of what happened, what they are responsible for, and how they can live with it now. Veronica is defiant with her penance and judgement, for her own transgression, what she may or may not have witnessed her father doing, the consequences of sharing that information, and the central crime she makes her own. Jim is lost, trying to deny his own guilt and comprehend his daughter’s. He frantically tries to explain how what she claimed she witnessed was impossible for him to commit, but who is he trying to convince? The connection between what he may or may not have done years ago, the betrayal Veronica felt when she accuses him, and the crime she goes to prison for seems tenuous at first, but it comes from the same damaged place. As hard as it can be to admit, that sense of guilt comes from a necessary, moral inkling. C.S. Lewis astutely saw our innate sense of right and wrong as a hint of God in the universe, that the world he created is of a moral design. Likewise, our own guilt can be a clue we need to what we did wrong, and how we have to make amends.

Which is why, of course, this has to be a Catholic film. In his own manner, Jim holds onto what he has from his past, even as it seems further distant. Video of his wife. The unusually long-lived pet bunny of Veronica’s he keeps care of during her incarceration, just a year or two shy of the world record for rabbits. And in the order of his religion, as nominal as it may have become, in the familiar duty of a Catholic husband and father, and ever the guilt of what he has done and failed to do, he finds something worth keeping. Something he has to keep.

In what amounts to the emotional climax, Jim finds himself invited to a private family party at an Armenian restaurant he reluctantly allowed to stay open and unexpectedly made the eponymous guest of honour. The quiet man is asked to make a toast, which the grateful, hospitable Armenians may regret. Jim made this feast possible, but in a drunken speech that ranges from heartbroken to outraged, he puts a damper on it, nearly breaking down as he asks questions that cannot be answered and makes demands that cannot be fulfilled. He ends by raising his glass of red wine, staring at it, and adding dutifully, ritually, almost like an afterthought, the unexpectedly religious benediction, “So…His Blood”.

Jim sees a reminder of the Eucharist, the sacrifice, how the Lord shed his own blood to wash away our sins. In a way, all these characters are seeking the same thing. The gentle priest, listening to the Byzantine turn of events and not sure the best way to comfort when he may know more than he wants to give up. The mourning daughter analyzing in requiem where her choices lead. And the man who sits in judgement before the meal is made, suddenly the guest and being judged himself. We can His Blood in the cup, but we must face our own guilt for it redeem us, and there’s the burden.